Chip crisis

How the automotive industry has fared during the chip shortage

Tracing back the development of the GlobalData forecasts from Q1 through to Q4 is instructive in understanding how the industry has been pressured by the chip shortage

W

hat initially started as a whisper in December 2020 that VW’s joint ventures in China were encountering difficulties in securing chip supplies soon subsumed the global industry affecting nearly every OEM in every country.

At the time of the Q1 forecast there was every expectation that the industry could quickly realign supplies and limit the fall out to Q1 and subsequently build back any lost volume throughout the year. At the time the forecast stood at 78.2m for the year, 13.3% ahead of 2020’s total but fully in line with SAAR rates in markets in Q4 2020.

Fast forward to Q4’s forecast, however, and we know that latent demand exceeds supply by some distance and that the industry’s window for building back lost production has all but disappeared. The net effect is that the forecast for 2021 now stands at 70.3m for the year, nearly 8m shy of initial expectations and barely above 2020’s level.

Central to the chip crisis has been the thesis that the auto sector has suffered due to the auto sector cancelling orders at the pandemic’s nadir allowing other sectors – like personal electronics – to queue jump and secure chip supplies for their products.

With 2021’s production levels set to be barely above 2020’s the point at when the chip call was made by the OEMs must have been when the opinion that the sector faced a U-shaped recession was ascendant. However, given that a six month lead time was cited for chip orders and that industry volumes were looking stronger from the end of Q2 2020 the industry should have been in a better place by now.

The fire at the Renesas chip plant in March 2021 and the shutdowns at downstream chip plants in Malaysia and Vietnam over the late summer, when COVID-19 infections surged, compounded the issues. Eventually, even Toyota, which had looked to have successfully weathered the storm, was drawn into the crisis. What the shortage has seen the OEMs do is focus on those segments where there’s a bigger contribution to the bottom line.

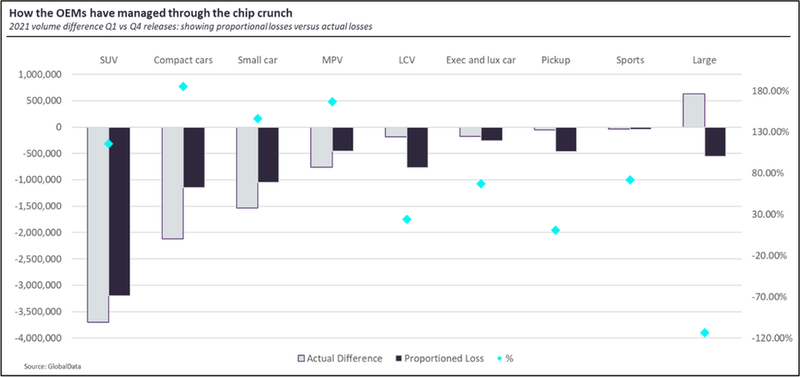

This is demonstrated in the chart below that shows disproportionate losses have been racked up by lower margin segments – compact cars (185% of losses that proportionality with overall volume would have dictated), MPVs (167%) and small cars (146%) – compared with more profitable large cars and pickups.

Such rationing of chips has potentially meant that fewer light vehicles will be produced this year than could have been if volume had been optimized rather that profits. This is because higher profit vehicles will typically consume more chips than less profitable vehicles.

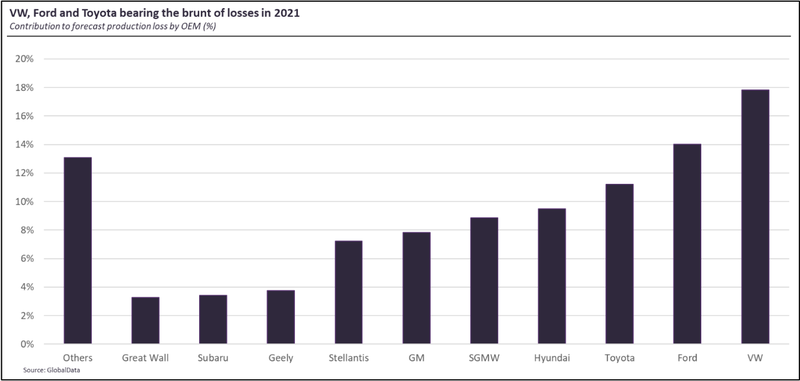

In terms of manufacturers, the Q4 forecast paints a picture whereby VW, Ford and Toyota have been most damaged in volume terms by the chip shortage. Of the 7.94m decrement to the 2021 forecast between Q1 and Q4 it is estimated that VW group has lost 1.4m in 2021 scheduled build volume contributing 17.8% to the total, while Ford has lost 1.1m a 14% contribution and Toyota 890,000 a 11.2% contribution. The top ten contributors to the loss by OEM are shown in the chart below.

What the chip crisis means for 2021 is that, despite its Q3 and Q4 issues, Toyota will cement its position as the number one automaker in the world. This seems fitting given the way it had managed to navigate through the early stages of the chip shortages due to supply chain strategies in place since the 2011 Fukushima disaster. With the company beginning to accelerate its BEV initiatives with its plans for a plethora of e-TNGA platform derivatives after the bZ4X it looks set to continue to be a formidable competitor for a good number of years yet.